Sometimes the most meaningful, significant gifts are given after one passes on.

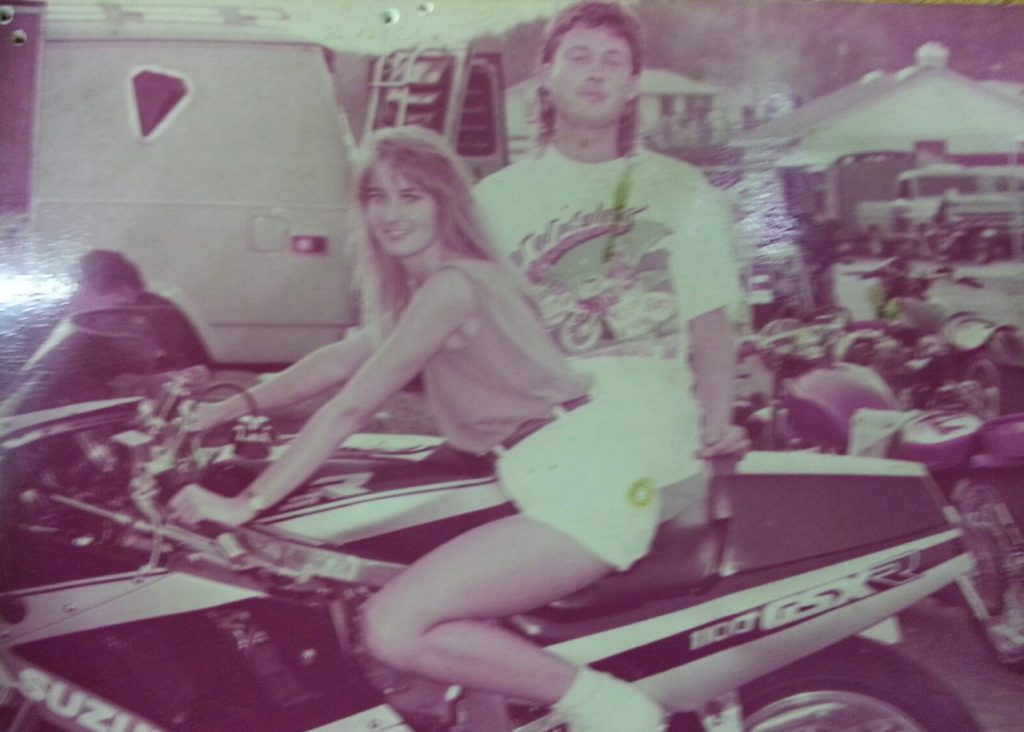

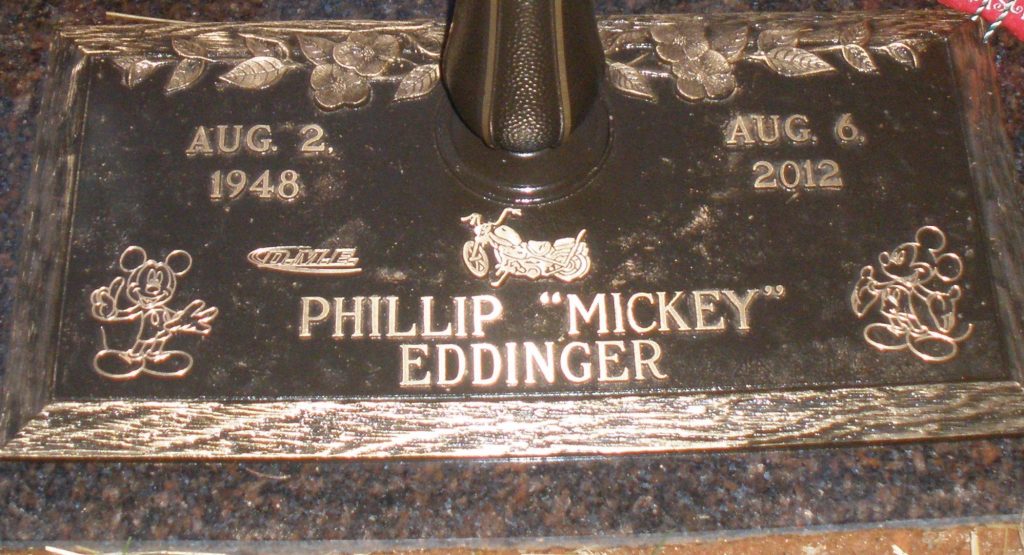

The late Phillip “Mickey” Eddinger shared his love and passion for motorcycles with his son Dimey.

Following Mickey’s untimely death in 2012, DME went on to become an empire and dominant force at the dragbike races.

Long before the creation of DME Racing, the father-son duo would spend the week operating a wheel shop and a construction business to pay the bills so they could spend just about every weekend at the racetrack. At work the labor was arduous and the hours were long. It was similar at the drag strip, but it was a lot more fun.

Some say when you do what you love for a living, it doesn’t feel much like work. Mickey was a firm believer in this philosophy and it was always his dream to see his son succeed in the motorcycle racing business. He also knew getting to that level would have to be earned and would not be without a lot of hard work.

The now extravagant DME operation started as a small pickup truck and an undersized open-trailer used for construction during the week. Even Eddinger admits some weekends he has flashbacks to his humble beginnings and is in awe of how far he has come.

Today it’s hard to miss the striking, luminous trailer which serves as a stable for the world’s quickest, most immaculate, stretched, wildly-painted, record-setting sportbikes. Alongside the championship-caliber motorcycles is long table full of top-notch, finely-crafted components for sale.

It was not an overnight success.

“A lot of people think we had all this handed to us and that is so far from the truth,” Eddinger said. “We paid our dues many times over.”

As a fitting tribute, Dimey’s Winston-Salem, N. C. based speed shop is in the same building his father once operated his business “Wheels by Mickey” out of.

“To know this was his dream means the world to me,” Eddinger said. “He raced motorcycles since I was a kid. To carry on to the next level from where he was is a big honor.”

When work permitted Mickey and his son would escape to the dragstrip to race a Kawasaki KZ or Honda 750. Mickey developed a name for himself in the pro ranks by helping legendary Top Fuel double-engine Harley racer Danny Johnson.

The drag strip wasn’t the only racing venue Mickey and Dimey frequented. His son was taught to maneuver a dirt bike shortly after he learned to walk. Dimey was an enormous success on the motocross track and worked his way up to B class. He even entered some Camel Supercross events on a 125 and 250.

“My dad was the type to put you in every moto he could. It was a lot of work,” Eddinger said. “When you went down you better get back up.”

Dimey raced and trained with some of the sport’s quickest riders like Damon Bradshaw. He continued to get faster, but as is the case with many aspiring motocross stars, injuries began to mount. A back injury at age 17 was severe enough to push him away from the whoops and jumps and into the land of reaction times and sixty-foots. Mickey offered his full support.

“He was excited to see me get into drag racing,” Eddinger said. “I just knew it was time to do something that wasn’t so hard on the body.”

Eddinger started drag racing on a 1992 Suzuki GSXR 1100 street bike and soon after built a remarkable Yamaha FZR 600, with the help of one of his childhood friends, who would go on to become an integral part of DME, Andy Sawyer.

“Andy was a kid who lived down the street and he would come over to the shop and hangout,” Eddinger said. “We would work on street bikes and dragbikes and get ready for the weekend.”

Sawyer developed a deep love for the mechanical side of racing. It was a perfect match. Dimey wanted to race and Sawyer wanted to build. Together they made a formidable team.

“We had offered him bikes to race but he just wanted to build and watch,” Eddinger said. “It worked out perfectly. We never had a conflict.”

The team’s first major project was the FZR. Both men were in awe of Blake Gann’s famous, small-bore Yamaha that could run impressive numbers. Eddinger found himself one for $500. Sawyer and Eddinger put a lot of labor and attention into the bike, put a turbo on it and ran 5.70s at 132 mph to the eighth-mile mark.

“It was unheard of at the time,” Eddinger said. “We were very proud of it.”

It wasn’t long after that the team decided to enter one of the hottest and most competitive classes at the time, Outlaw Pro Street, featuring a massive 75-inch wheel base, no wheelie-bars, a minuscule seven-inch slick and cases of nitrous bottles.

“We went to Piedmont (Dragway, Julian, N.C.) one Friday night and Shawn Gann was there on his Outlaw Pro Street Bike. We had already built one for a friend. I saw Shawn was making the decisions on his bike and I’m the kind of guy who likes to make my decisions. I said shoot that’s what I want to do.”

Almost as quick as Shawn Gann erupted down the quarter-mile that Friday night, Eddinger and Sawyer were headed for the pro ranks.

It proved to be a demanding and strenuous transition. At its peak Outlaw Pro Street would see more than 20 entries at hotbed tracks like Rockingham Dragway in N.C. and Maryland International Raceway. Just to qualify was a grueling challenge. It was hands-on, and often times costly, on-the-job training for DME.

“We tore up so much stuff. And looking back, compared to what we know now, it’s depressing to think about how much stuff we went to the track with and came back with a pile of junk,” Eddinger said. “I am really appreciative of the people who helped us out. I remember Joe Franco helped us a lot and that meant the world to me. Today I want to be that person and help people.”

Eventually the team scoured its chassis in search of quicker E.T.s. It worked, but often extreme innovation can create controversy. Some in the class did not approve of Eddinger’s new backbone and how far his motor was pushed up in the frame.

The debate proved to be the impetus for something that would revolutionize DME. The company was ready to pull away from its bread and butter and trade the nitrous in for a turbo.

“I was driving down the road and I called Andy and said what if we build a turbo Outlaw Pro Street? He was like man you are crazy. We have too much in this nitrous deal. We hung up and I said oh well,” Eddinger said. “A couple hours later Andy called me back and said let’s do it.”

It was an over-the-winter build. DME made nearly all the components from the throttle bodies to many internal engine components. It was DME’s first electronic fuel injection race bike.

“Andy is the kind of person that will sit down and figure it out,” Eddinger said. “We spent every dime we had to build the bike. There was no backing up.”

Like all of Dimey’s motorcycles, the machine was a work of art. Mechanically the team was stymied at the track when the bike wouldn’t eclipse 9,500 RPMs.

“Sebastian at NLR grabbed us and told us we had the wrong boost controller on it,” Eddinger said “We went down to his house in Alabama and put it on the dyno.”

The improvement was immediately evident. At the following race Dimey recorded an extraordinary 7.04, marking the first Outlaw Pro Street run in the 7.0s. It proved to be a number Dimey would not be able to savor for long.

“At that race they (MIROCK) had a meeting without us and made the decision to outlaw the turbo bikes. They said the bike was too far ahead of its time,” Eddinger said. “It put a really bad taste in my mouth. I was furious. I was ready to throw the towel in.”

Despite the disappoint Dimey pressed on, but as his business and family grew and he glanced back at a career that included a pair of runner-up finishes in the points and he had another epiphany. It was time to get off the bike and focus on DME. Dimey concluded his racing became counterproductive to his business.

“I was having a hard time focusing on the starting line. I had so much pressure on me knowing everyone spent a lot of time working on these bikes and if I would go up and red light or do something crazy I would beat myself up all week,” Eddinger said. “When you get married and have kids there is a lot more to think about. I still wanted that number one plate. I needed somebody who could eat, breath and sleep motorcycle racing like I used to.”

That rider ended up being a light and talented jockey out of Delaware who came from a racing family, Joey Gladstone.

After amassing multiple championships and setting numerous records, Eddinger knows he made a great choice.

“There are times I still want to ride, but I wake up in the morning knowing I made the right decision,” Eddinger said. “I have to thank everyone for being with me for all these years.”

Dimey is just as satisfied with the advancement of his company as he is with his championship titles.

“When Andy and I decided to do this full time we knew we had to go about in a different way. Dealerships can make great money but speed shops struggle. We try to supply the motorcycle shops with bolt on products and chassis components.” Eddinger said.

With a thriving business and a talented group of team riders including Gladstone, Terence Angela, Jason Dunigan, Christopher Connely, Jeremy Teasley, Dustin Lee, European racers Steve and Jenna Venables and more, Dimey knows he has a lot to be thankful for.

DME Racing found its way and Dimey knows his father would be proud.

“He would be ecstatic,” Eddinger said. “This was his dream to make a living off drag racing.”

The spirit of Mickey lives on at the track.

Great insightful article!

Dimmey,Really all i can say is your Dad was A1 in my book. Good friend that would give you the shirt off his back.I’ve rode with him many times. And also came and watched you race.Thanks,For sharing this post. Good Luck And God Bless…